An Advocate of the People: The New Exhibit at the Modjeska Monteith Simkins House

Wednesday, February 3rd 2021

Modjeska Monteith Simkins, born in Columbia, was one of South Carolina’s most significant human rights advocates. During the pivotal civil rights movement, Simkins served as secretary in the South Carolina NAACP, where she helped advance voting rights and desegregate schools in the state. Her career spanned a lifetime of advocacy and service, including time as a teacher, health educator, fundraiser, business owner, journalist, and community organizer.

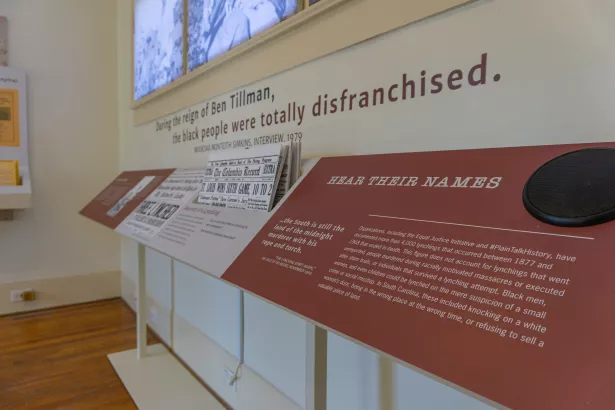

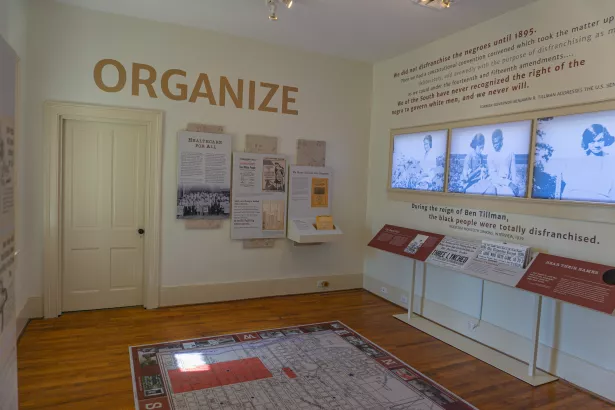

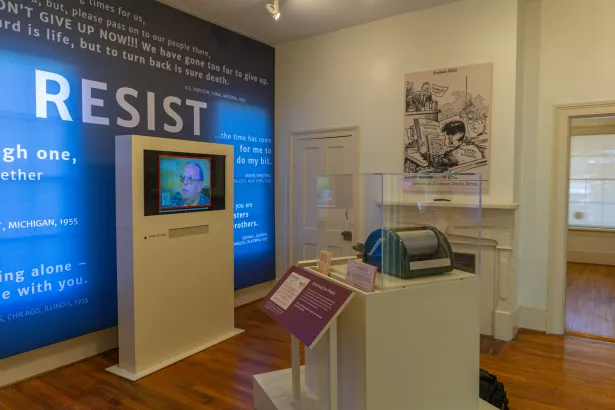

Historic Columbia recently completed the exhibit “An Advocate of the People” after multiple years of research and in collaboration with the Monteith family. This work resulted in a multimedia experience that documents Simkins’ upbringing and career as a public health worker and state secretary of the SC NAACP through the lens of the long civil rights movement.

While the exhibit is not open to the public at this time due to the ongoing pandemic, we want to bring the history in “An Advocate of the People” to you online -- in the spirit of Simkins’ unyielding pursuit for justice, in tribute to the importance of her work in expanding equal rights, in an effort to understand today’s current events through the past, and with a desire to inspire future advocates.

Over the next several weeks, we’ll share highlights from the exhibit on our blog and social media (Facebook, Twitter and Instagram). Now, let’s dive in.

Image courtesy of South Caroliniana Library

Who was Modjeska Monteith Simkins?

The exhibit documents Simkins’ life and career beginning with her formative years in the Jim Crow South and especially focusing on her essential role in South Carolina’s civil rights movement.

Did you know?

- Modjeska Monteith taught mathematics at the segregated Booker T. Washington High School before her marriage to Andrew W. Simkins, Jr. in 1929. Because married women were not allowed to teach, Simkins was dismissed from her position, but continued to desire work and a career.

- In 1931, the South Carolina Tuberculosis Association (SCTA) hired Simkins as its first Director of Negro Work. Her work with the SCTA, in particular, exposed the middle-class Simkins to the abject poverty and poor health of rural Black Americans, a result of pervasive and systemic inequality.

- In 1941, Simkins became the first female secretary of the South Carolina State Conference of Branches of the NAACP (SC NAACP), an organization she helped organize two years earlier. Key cases during Simkins’ tenure at the SC NAACP included the fight for equal pay for Black teachers (Duval v. Seigneus and Thompson v. Gibbes et al.), the fight to end the all-white Democratic primary in South Carolina (Elmore v. Rice), and the fight to end segregation in public schools (Briggs v. Elliott, which would become part of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education).

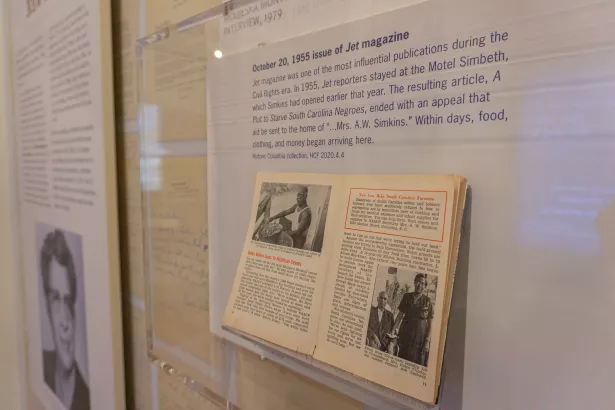

- Simkins owned and operated Motel Simbeth, a place of rest for Black tourists listed in the famous Green Book. The hotel was not only a stop for weary travelers, but also a location for civil rights leaders to stay, including Martin Luther King, Jr., during visits to the state capital.

- In the 1940s, Simkins served as a key advisor to the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC), an organization founded in 1937. Unlike the NAACP, which focused on legal strategy, the SNYC used direct action protests to demand human rights for all. Their strategies were a forerunner to the 1960s youth-led civil rights movement. Simkins saw its young leaders as the future of America.

What is special about Simkins’ house?

Purchased at auction on July 4, 1932, this home was a gathering place for civil rights activists for nearly 60 years until Simkins’ death in 1992. The home also served as a place for developing and organizing legal strategies on issues with local, state, and national significance.

“Thurgood Marshall always stayed in my home, as did the others as far as my home could accommodate. We had two extra bedrooms. Some lawyers stayed there, and the others stayed across the street from me. But they would have their meals and jam sessions around the table in my home.” Modjeska Monteith Simkins, Interview, 1979

In 2006, Historic Columbia took over the stewardship of the site from the Collaborative for Community Trust, which saved the site from demolition. Due to receiving an African American Civil Rights Grant from the Historic Preservation Fund administered by the National Park Service, Historic Columbia later broke ground on a major rehabilitation project for the site in late 2019. Improvements included repairs to the house’s foundation, brick, plaster, trim and doors, and windows. A handicap parking space and ramp were also put in place for increased accessibility to the building.

What is important about the new exhibit?

“An Advocate of the People” highlights Simkins’ role in navigating discrimination and oppression of the Jim Crow period while organizing Black South Carolinians to fight for — and win — equality on multiple fronts. The work of Black citizens like Simkins during this time period brought American democracy closer to the ideals espoused by the Founding Fathers than at any other point in the country’s history. The exhibit content invites visitors to connect the values of Simkins and her contemporaries to those of future generations of activists while closely examining the central — and complicated — role that the media has played in the struggle for equality.

In partnership with the family of Modjeska Monteith Simkins, this exhibit returns the home to a place that is central to engagement and action for the community. Simkins worked tirelessly for equal rights and justice, and her personal letterhead once included the phrase, “An advocate of the people.” By using her life as a lens through which we view historical inequality, the impact of organizing, and the power of protest, her home will once again aid others in advocating for the rights of humans.

What action will you take?

The fight for equality is never finished. Over the next several weeks, consider how you can keep the spirit of Modjeska Monteith Simkins alive today.

This material was produced with assistance from the Historic Preservation Fund, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior.