Quest for a Berry is Finally Fruitful

Wednesday, July 31st 2024

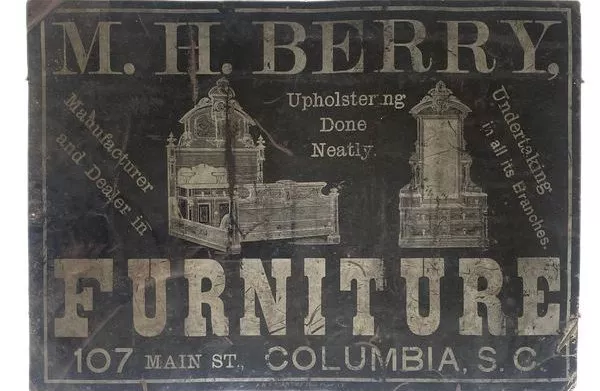

Image above: Milo Berry Shop Sign (HCF2024.3.1). Berry operated at 107 Main Street from the mid-1870s to the early 1880s. This small metal sign may have been used to mark the front door of Berry’s shop.

It is human nature to get excited about new additions to one’s home. Typically, “new” refers to items fresh off the conveyer belt—the things that have not yet been used. In the world of collections, we get excited about the new old acquisitions that come to the museum. This is especially true when the items we receive have been on our radar for a long time. This summer, after years of waiting patiently, staff at Historic Columbia acquired several objects for the institution’s permanent collection related to a prominent nineteenth-century Columbia cabinetmaker, Milo Hoyt Berry. We’re excited to share information about these new objects with you, as well as discuss Berry’s legacy in Columbia.

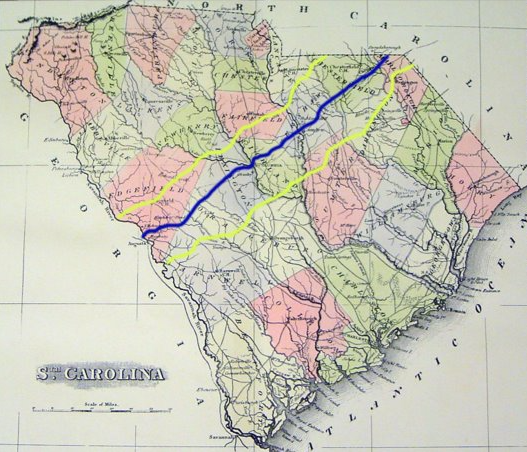

Berry’s life first came to the attention of HC’s Director of Preservation, John Sherrer, (then the Director of Historic Properties and Interpretation) nearly 20 years ago when he was researching artisans that operated along the South Carolina fall line. Fall lines are geographic features where an elevated region, such as the Piedmont, intersects with a lower region, such as the Lowcountry. Commonly seen along fall lines are waterways and waterfalls. In South Carolina, Columbia sits in the fall line along the Congaree River, with Greenville situated in the Piedmont and Charleston on the edge of the Lowcountry.

As a scholar for the newly created South Carolina Fall Line Consortium—a committee he co-created in 2002 of staff from various Richland County museums and archives—Sherrer researched several cabinetmakers operating within the state’s fall line region during the late 1700s through 1800s. This research highlighted the contributions of many artisans who shaped the Palmetto State’s material culture—chief among them was Milo Berry, a New Jersey transplant who relocated to Columbia by 1843. Objects attributed to Berry existed in various private collections and within the walls of other historical institutions, allowing Sherrer to examine these pieces in relation to his research.

Despite years of searching, Historic Columbia was unable to acquire a Berry piece for its museum collection. However, in 2024, HC was approached by a donor committed to gifting several objects to Historic Columbia. This donor came from a family of Berry’s direct descendants with whom Sherrer had built a relationship with two decades prior.

Dusting off research done by Sherrer and pairing it with modern-day means of study, the Historic Columbia Collections team began refreshing its knowledge about these objects and Berry himself.

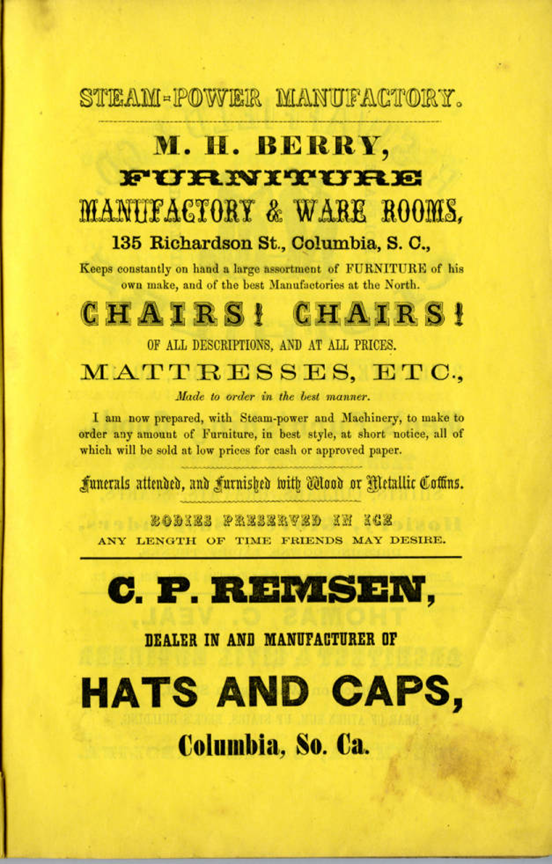

Berry’s Business

Milo Hoyt Berry (1819-1907) came to Charleston from Newark, New Jersey, around 1843 with his new bride, Harriet Meiggs (1820-1849). Having already established himself as a cabinetmaker in the North, he secured a contract to furnish the Charleston Hotel (demolished in 1960). Upon completing the project, Berry began making furniture in Columbia beginning in either 1844 or 1845. At various times in his early career and during the Civil War, Berry partnered with other merchants such as Jeremiah Price (1816-1889) and George Symmers (1832-1882). Berry remained in the furniture-making business until his retirement in 1903 at the age of 84. He died four years later.

A growing city like Columbia needed more than one furniture maker to supply the town. Of course, residents who could afford it could purchase their furniture outside of the city, state, and even country, yet the demand for locally made furniture was high enough for several cabinetmakers to operate out of Columbia during the mid- to late-1800s. Early competitors of Berry’s were Abraham C. Squier (1805-1887) and George Bowers (1807-1866). Both Bowers and Squier came to Columbia from New Jersey, settling in the city a few years before Berry. Although Bowers died in 1866, Squier remained a competitor from 1859 through at least 1891. By 1895, Squier seems to have closed his furniture business and instead operated a large grocery store, Lorick & Lowrance Mercantile.

Like other nineteenth-century cabinetmakers, Berry also operated as an undertaker. This was not unusual, as the construction methods and materials for coffin making were similar to those used in furniture production. Indeed, Berry advertised that he used walnut in both his furniture and coffins. Not all furniture makers competing with Berry were also undertakers. According to city directories from the latter half of the 1800s, neither Bowers nor Squier seemed to cater to those no longer living. However, lesser-known furniture merchants like the Fagon Brothers, Rhodes and Van Metre, and the Funderburks did sell coffins. Of these, the Van Metres grew to local prominence during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Despite numerous fires and the destruction of his cabinet shop and warerooms during the Civil War, Berry persevered in his endeavors. While his operation was listed at different locations throughout his career—135 Richardson Street (c.1850–c.1868), 107 North Richardson Street (c.1870–c.1880), 115 North Richardson Street (c.1880–1991), and 1440 Main Street (c.1892–1903)—these locations appear to be one in the same. As Columbia grew, street names and numbers fluctuated. Berry retired in 1903, the same year James M. McCormick and John D. Pletscher established their own undertaking operation at 1440 Main Street. They did not make furniture.

Along with a sign advertising Berry’s shop at 107 North Richardson Street, the donor also gifted HC a washstand signed by Berry. Underneath the washstand’s marble top, written on the secondary wood from a recycled shipping crate marked with “Charleston” in the top right corner), is “MH Berry, Columbia SC, [illegible] RR [illegible]” and a red “55”. What is arguably more interesting is that the sign advertising Berry’s business features a washstand that is nearly identical to the one the HC recently acquired (look within the large bedstead pictured on the sign).

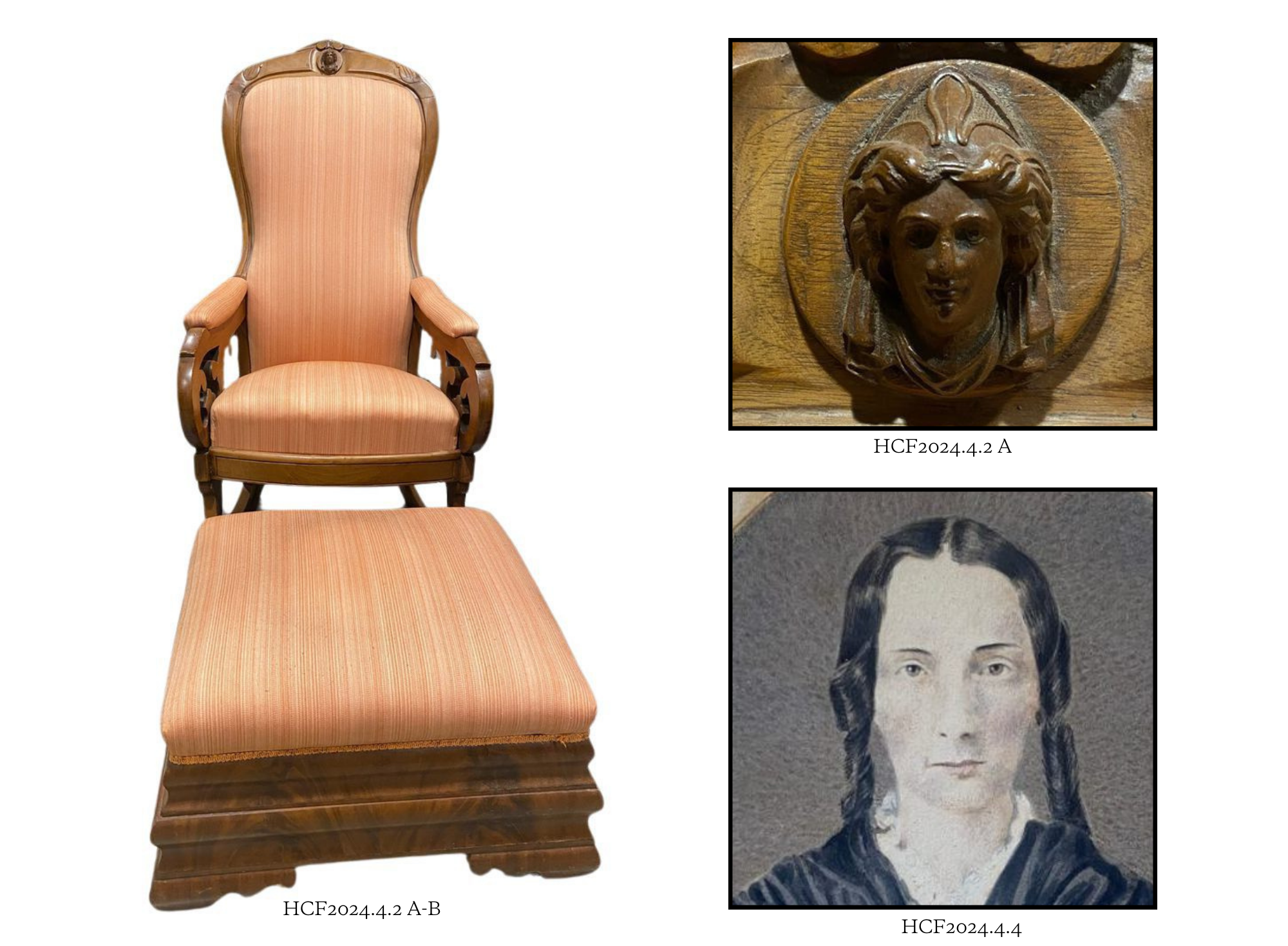

While Berry also made various types of chairs, one such chair from the donor came with interesting family lore: the carving on this rocker (which came with a footstool) is said to have been carved in his first wife’s likeness. While not as common as carvings of flowers and fruits, depictions of women were also seen on rockers during the Victorian era. At this point, more research is being done to strengthen the validity of the claim.

Berry’s Brides

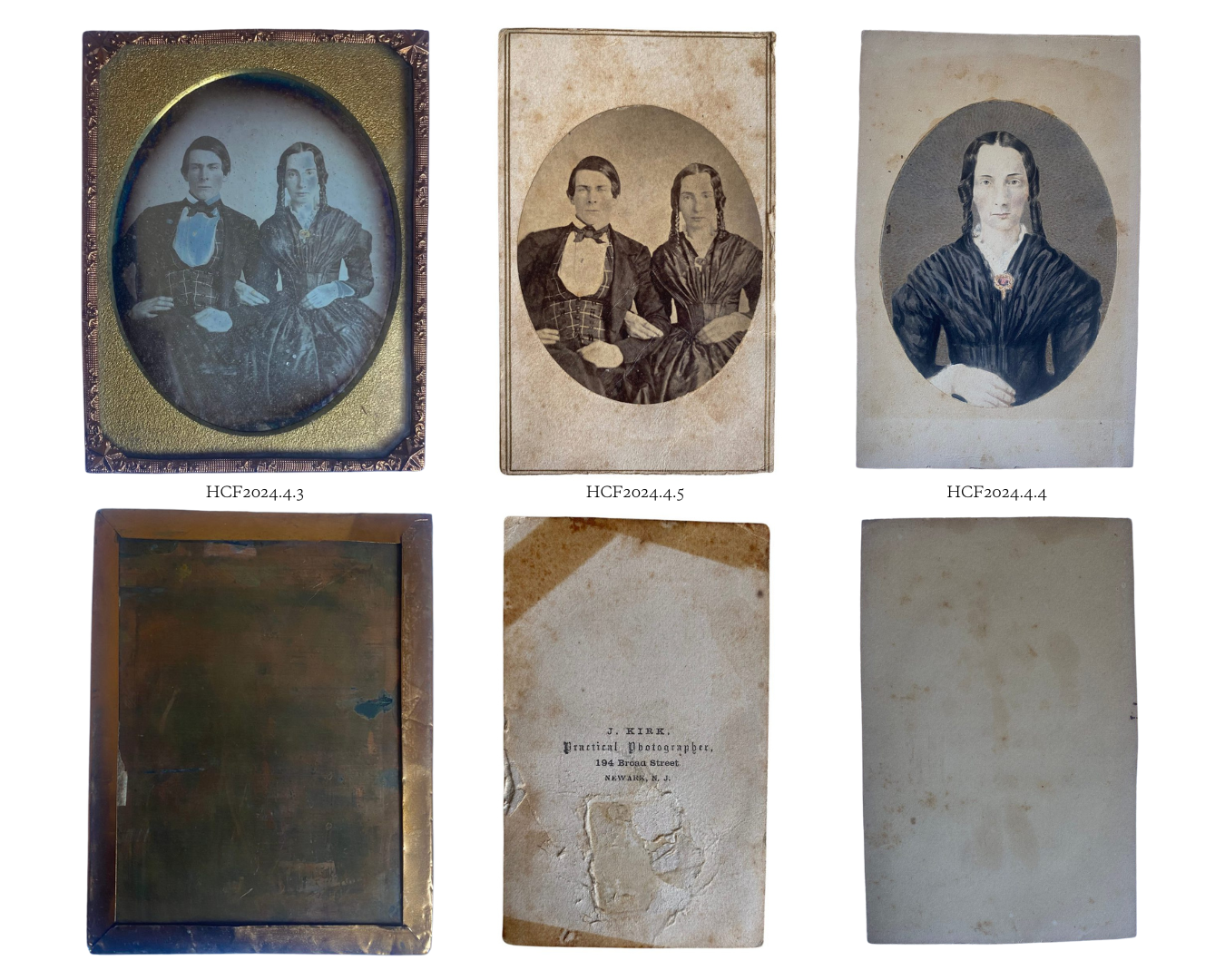

Harriet, Berry’s first wife, unfortunately died at the age of 29. She and her husband appear in both a daguerreotype (HCF2024.4.3) and a cabinet card (HCF2024.4.5) that HC recently acquired. Invented in 1837, daguerreotypes were the first publicly available type of photographic likenesses. Popular in the 1840s and 1850s, they were soon replaced with their sister-method of photography, the ambrotype. This object must date between 1843 (when the two married) and 1849 (when Harriet died). As for the cabinet card, a later style of photography in which a small photograph was mounted on cardstock, it was likely completed in the 1860s—nearly 20 years after Harriet’s death—when the photographer, Joseph Kirk (b.1830) of Newark, began his operation. While not yet confirmed, an accompanying drawing of Harriet (HCF2024.4.4) may have also been completed by Kirk at the same time.

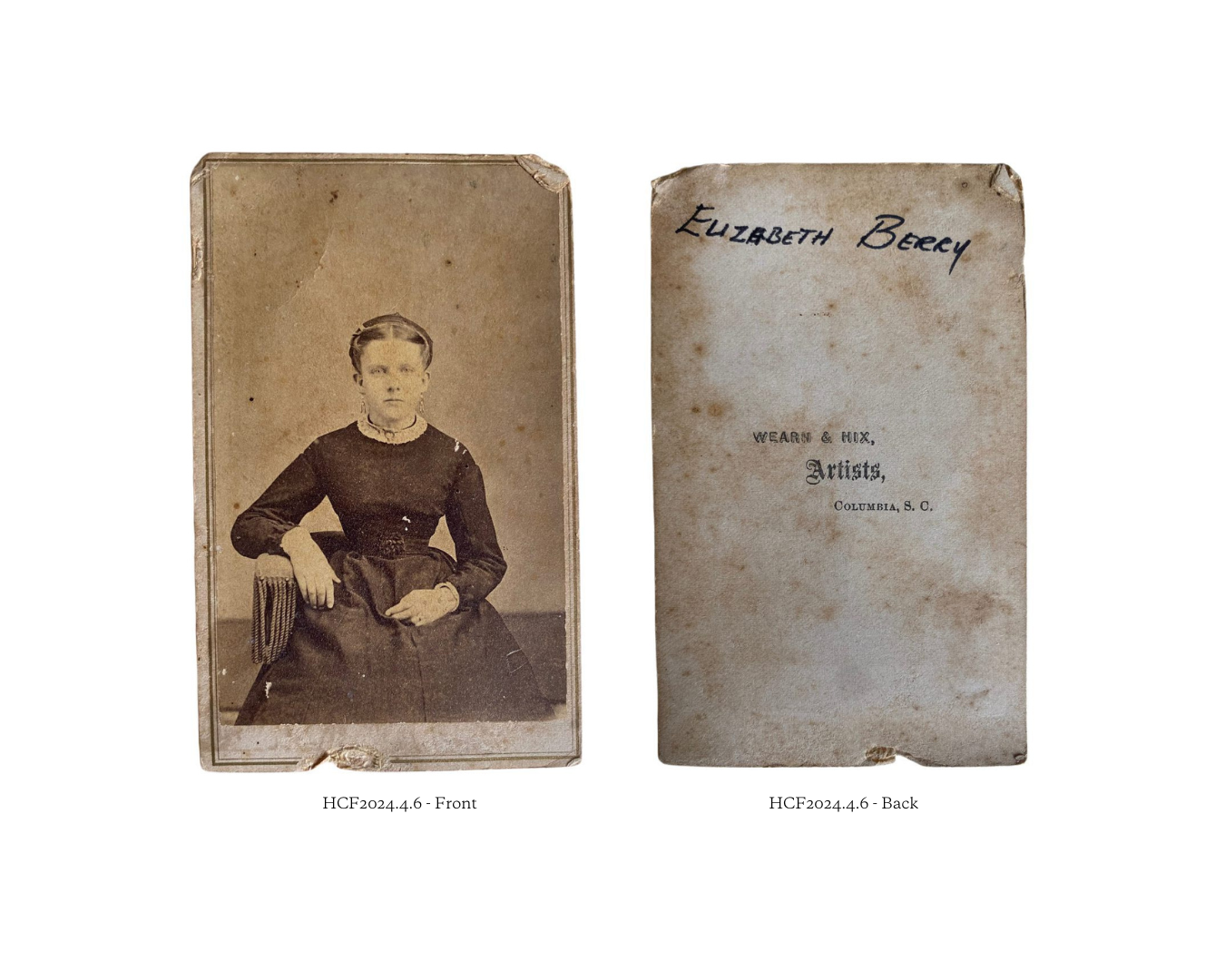

Widowed with at least four young children, Berry turned to his sister-in-law, Julia Meiggs (1822-1906), whom he married in 1849, just five months after her sister’s premature demise. Julia and Milo had a few children together, caring for them as well as the four from his previous marriage. It does not appear that any of Berry’s children were interested in their father’s business (only three of his children outlived him). Many of Berry’s children remained in the Columbia area throughout their lives, including one of his daughters, Elizabeth Ayers Berry (1852-1930), who is pictured in another cabinet card (HCF2024.4.6).

Milo Berry had a long life in Columbia, and due to the knowledge, forethought, and care of his descendants, aspects of his career and personal life can now live on for additional generations. As we near the 180th anniversary of the artisan’s arrival to Columbia, Historic Columbia is excited to share these objects with you. The washstand and the rocker will soon be on display in the Hampton-Preston Mansion, while the other recent acquisitions are being considered for display in an upcoming exhibition. Until then, more information regarding their history can be found in our online database.

Explore HC's

Online Collection

Did you know that Historic Columbia maintains a 4,000 item collection of objects of various mediums and sizes that tell the stories of those who lived and worked in Columbia and Richland County? Explore the collection online and learn more!