Park It: Columbia’s Green Spaces Reconstructed

Friday, October 26th 2018

If Forest Acres is a City Apart, then Columbia is a City of Parks.

There’s Finlay Park in the heart of downtown, the Riverwalk along the Congaree, the tail-wagging Bark Park in NoMa, Riverbanks Zoo and the Botanical Garden, Carolina’s Horseshoe, and Main Street’s cute-as-a-button pocket park. Oh – and Congaree, South Carolina’s only National Park.

Today, we might consider these communal spaces as just that — communal. A space for the greater Cola community to gather, play, picnic, and relax. A green space where the tree roots run as deep as our love for the city.

But these spaces haven’t always been this way.

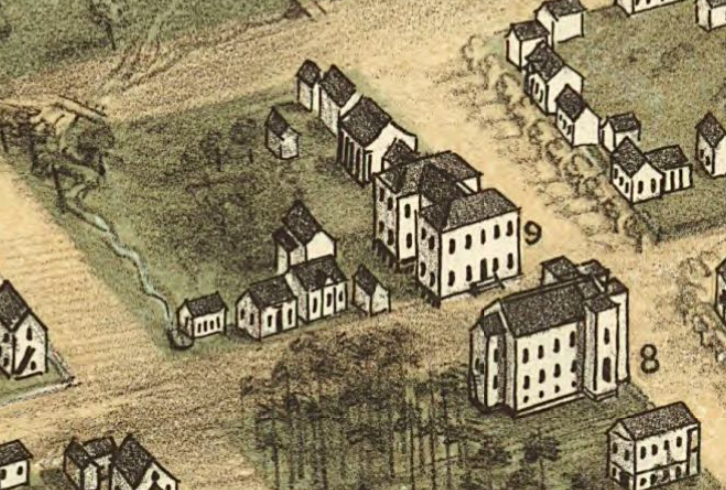

Parks in Columbia date back to the early 1800s, when elite antebellum planters created pleasure gardens on their own lands and visited “resorts” at places like Lightwood Knot Springs and Minervaville. These parks were exclusionary by nature—a way to demonstrate wealth, status, and power.

Columbia’s first public park was established sometime in the late 1840s by Algernon Sidney Johnson. Sidney Park remained a bright spot until 1899, when its pathways, fountains and mature plantings were destroyed to make way for railroad tracks and warehouses that ushered in the era of Seaboard Park, so named for its retooling for transportation purposes.

The turn of the 20th century brought much-appreciated relief, when Columbia’s Irwin Park Zoo captured citizens’ attention in 1911. Yet, for many years, only some Columbians could visit the menagerie, which included camels, deer, exotic waterfowl, and two wildcats named Lu and Tom. In 1915, the city finally designated Tuesdays and Thursdays as days when black Columbians could visit the zoo and surrounding gardens. Enforced segregation would endure in the city’s public spaces for another 50 years.

By 1946, only three parks – Old Howard, St. Anna’s and the new Seegers Park – were available to African Americans. Old Howard, as the site of the original Howard School, had long served as a segregated space. Formerly located at the northwest corner of Hampton and Lincoln streets, the school opened in 1869 with partial funding from the Freedmen’s Bureau. For nearly 50 years, it served as the state’s first—and only—public school for African Americans.

The school moved to a new facility at 1716 Williams Street in 1924. Although the main structure was demolished, the site became known as Old Howard Park, and at least one outbuilding became the recreation center known as Fun Teen Park, which opened October 11, 1948.

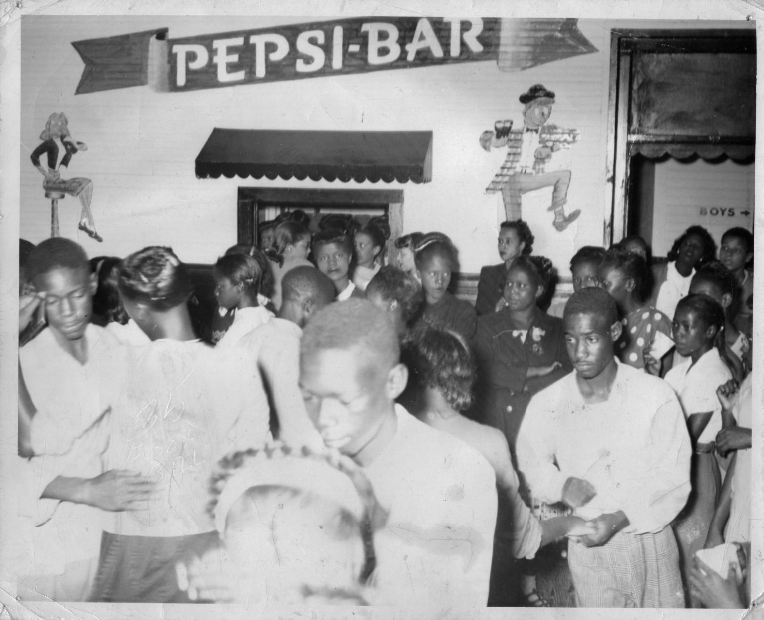

The park, which included a modern snack bar and a newly constructed spray pool and patio, sought to provide amenities to African American children and teens who were barred from using Columbia’s other parks, including Maxey Gregg and Valley Park. Here, teens attend a dance at the park’s recreation center in 1950.

In 1973, the park’s land was deeded to the Columbia Housing Authority as part of an urban renewal project in the area. This structure, since demolished, was the last remaining building associated with the original Howard School.

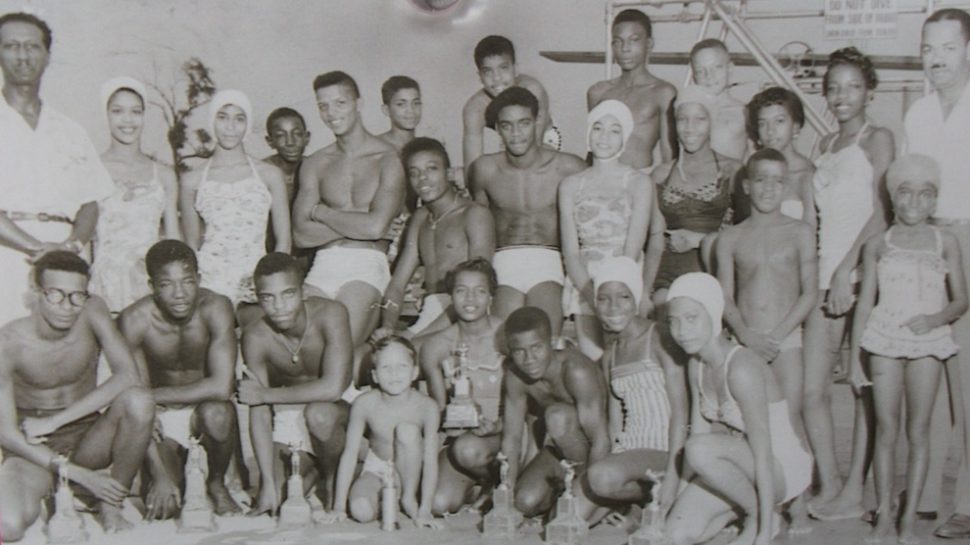

The creation of Fun Teen Park was part of a larger parks project aimed at improving life for all Columbians. Between 1946 and 1950, the city upgraded facilities at all of its parks, including the construction of two $200,000 swimming pools – one for white citizens at Maxey Gregg Park, and the other for black citizens at Seegers Park. After the pool’s opening in 1950, Seegers Park began offering free swimming lessons to African Americans.

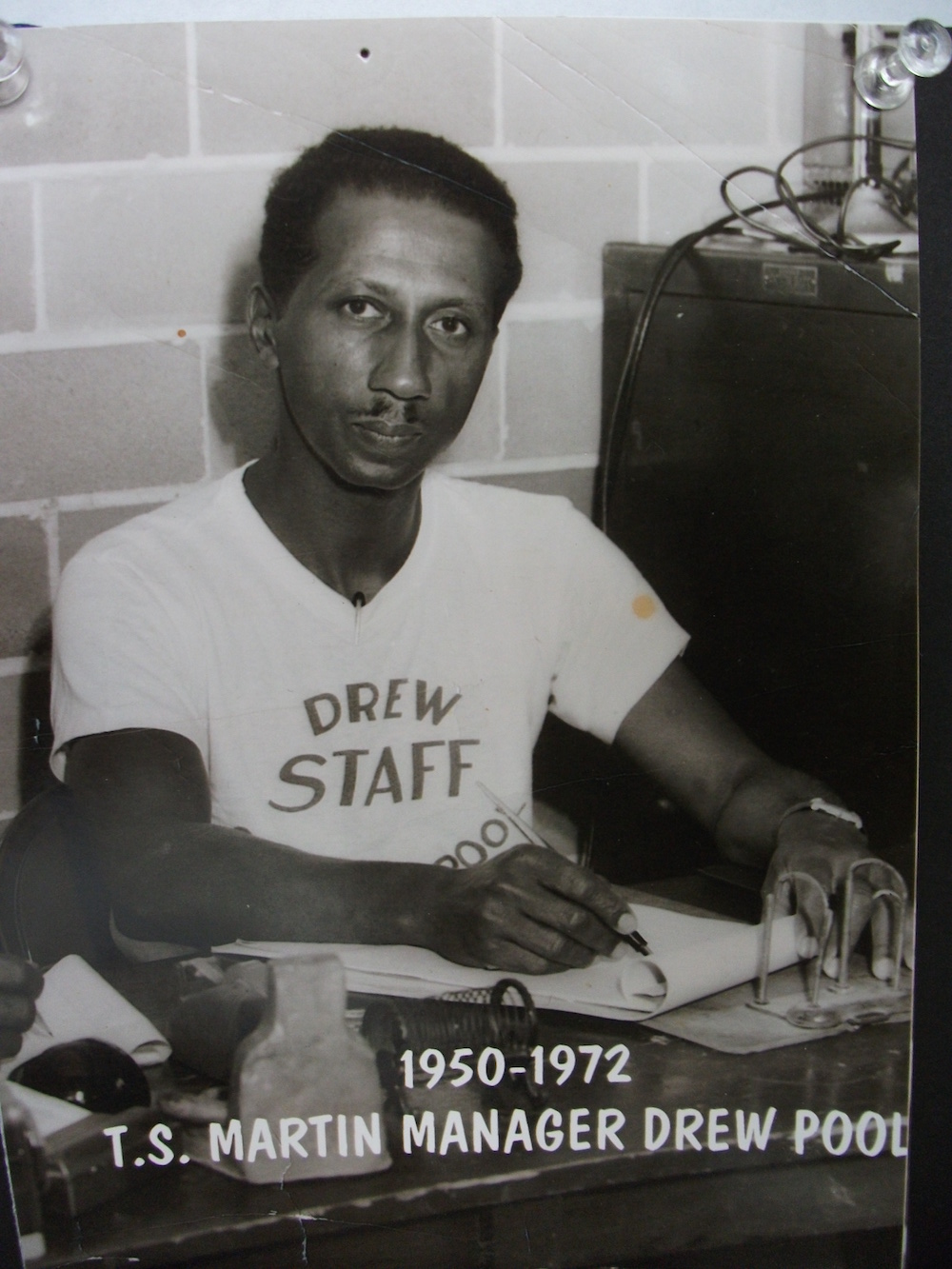

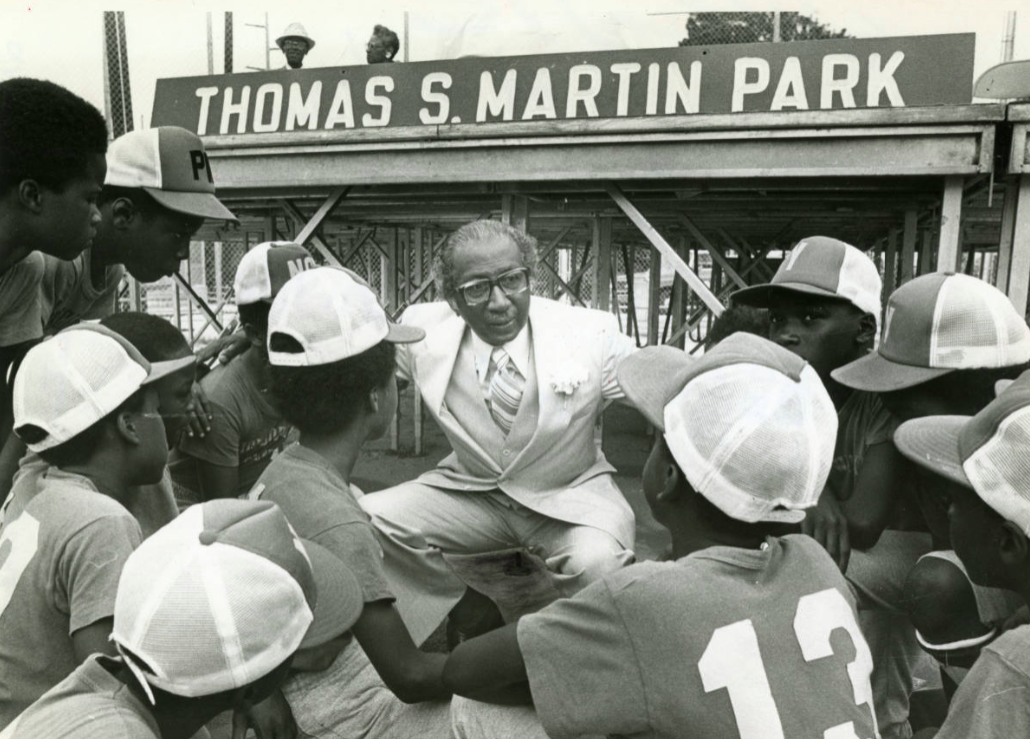

The park was renamed in honor of Dr. Charles A. Drew in 1952, and around that time the Drew Park Pool Sharks, a competitive swim team, was established. Led by prominent educator Thomas S. Martin (at left) and his brother-in-law, Charles F. Bolden, Sr. (at right), the Sharks competed at meets across the South.

T.S. Martin served as the manager of the Drew Park Pool from 1950 until 1972. A lifelong educator who taught physical education and science at Booker T. Washington High School, Martin dedicated his life to improving the physical health and wellbeing of black students across Columbia. The city created and dedicated a new park in his honor in 1980.

Charles F. Bolden, Sr. coached alongside Martin at the Drew Pool, but also served as the football coach for Booker T. Washington’s greatest rival, C.A. Johnson High School. He married Ethel Martin, a librarian at W.A. Perry Middle School who became the first African American professional at Dreher High School. Their son, Charles F. Bolden, Jr., would become arguably Columbia’s most accomplished citizen.

Charles F. Bolden, Jr., graduated from C.A. Johnson High School in 1964 and the United States Naval Academy in 1968. He served in Vietnam and was selected as an astronaut candidate in 1980. During his tenure with NASA, Bolden piloted and commanded multiple missions, including the Space Shuttle Discovery (1990) mission that launched the Hubble Space Telescope. In 2009, President Barack Obama appointed Bolden as the 12th Administrator of NASA, a position he held until his retirement in January 2017.

This article is a part of Historic Columbia's #TBT collaboration with Cola Today.

Learn More

If you’d like to learn more about Columbia’s neighborhood parks and the people who enjoyed them, check out Historic Columbia’s free online tours. You never know what new things you might learn in (or about) your own backyard.