Connected by a Thread

Thursday, February 23rd 2023

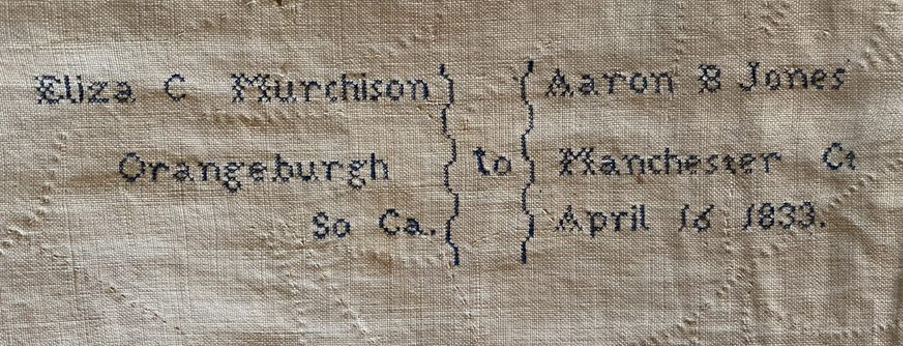

Image above: Sampler by Jane M. Murchison, currently on display at the Robert Mills House. Historic Columbia collection, HCF1970.25.1.

As Historic Columbia observes Women’s History Month, we acknowledge and celebrate two women whose material culture survive within our collection. It is often difficult to uncover information about women in the early nineteenth century, as many were hidden in the shadow of their husbands, brothers, and fathers; in other words, their lives were rarely recorded to the degree of their male family members. However, most women were trained in household tasks such as sewing and often completed remarkable work. Depending on their socioeconomic status, these women may have crafted textile pieces purely for show or for utilitarian purposes. The textile collection of Historic Columbia contains a variety of pieces, all of which shed light on the lives of the women who made them.

If you have visited the Robert Mills House recently, you would have seen this sampler on display in the East Parlor. In the nineteenth century, samplers were a common part of handiwork training for girls as young as five years old. As the name suggests, samplers served to display a sample of the embroidery skills that may be required of a lady of the house. These pieces are often signed and dated and may include proverbs, poems, or bible verses.

The Gift of Time

Jane M. Murchison completed this sampler in 1826 when she was only eight years old. Certain details reveal that Jane came from a family of some means, allowing her to have the time to practice her stitches.

The fact that Jane had both the time to create a sampler of this quality indicates that her family had other in the household performing daily chores. Had Jane been of a lower socioeconomic status, she would have still been taught how to sew, but her stitches would have no need to be as artistic. Instead, those sewing skills would be used to do quick mends on clothing and to create simple blankets and quilts for warmth. Additionally, any spare thread and fabric would not have been wasted to create such finery, as that spare cloth and thread of a variety of colors would have been an additional expense not all families would have been able to afford.

It wasn’t as though all young girls at this time would have been taught at this age to read or write either, making their need to practice their letters in any way nonexistent. Not only does Jane’s work include letters and numbers, indicating some formal education, but also additional colorful decorations such as the mushrooms and the foliage on the lower half of the sampler.

Who was Jane Murchison?

But what else can we learn about Jane’s life? Based on the date and her age at the time of the piece’s completion, we know she was born around 1818. However, identifying further details is difficult without knowing where she was living or the names of other family members. Unsurprisingly, initial genealogical searches for “Jane Murchison” proved unsuccessful— due to her young age, she would likely not appear until the 1850 US Census, and even then, it would be more likely that she would appear under an unknown married name.

Fortunately, clues from another textile in HC’s collection unveiled more details about Jane’s life.

A Murchison Family Quilt

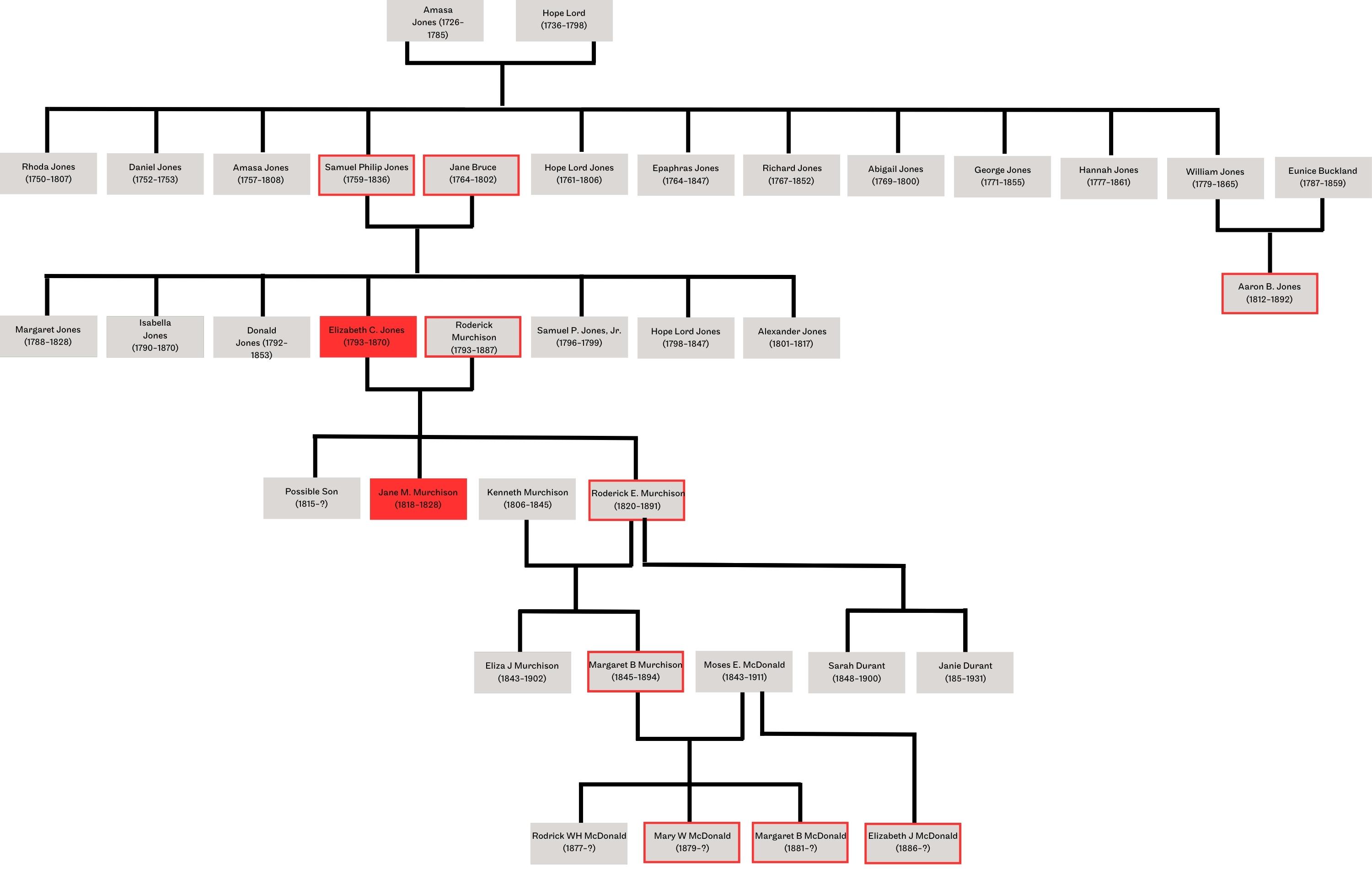

While it is less common for a quilt to be signed than a sampler, this large chintz quilt, currently on displayed in the Robert Mills House, was signed and dated in cross-stitching on the reserve by Eliza C. Murchison in 1833. Unlike Jane’s sampler, it reveals some additional details, including that Eliza was living in “Orangeburgh, So Ca” at the time, as well as that it was gifted to Aaron B. Jones of Manchester, Connecticut. While that label provides information about the purpose of the piece, who made it, when it was made and where, the construction of the quilt adds information as to Eliza’s socioeconomic status.

An Expensive Fabric

The fabric used as the boarder on top of Eliza’s quilt is chintz, a very expensive, likely imported fabric. Originating in India before being imported to Europe, chintz was originally used as draperies and furnishing coverings in the 1600s. Its floral design, created by stamping a woodblock or even hand painting the design with dye and mordant onto fabric before rinsing it with rice water and sealing it with a type of wax, was so popular that some European countries actually banned it as an import to protect their own textile production and sales. It was also a difficult and time-consuming method to reproduce. England eventually became successful in creating their own chintz with a large amount of enslaved labor and began to export it to other countries, including the colonies; the United States did not join in chintz production until the 1830s. While it is colorfast and a sturdy fabric, it would rarely be used for utilitarian purposes, but rather as a display of wealth and taste in upper-class homes.

Expert Stitchwork

Eliza was quite skilled with needle and thread, making such fine stitches that 12 of them could fit into one inch of the quilting. For comparison, the standard of what is still considered “good” quilting averages 8 stitches-per-inch. Not all women would have had the time or the patience to include such a high stitch-count in a quilt, especially one of this size (98.5 inches by 98 inches). While we know from the 1840 census record that Eliza enslaved 10 people, the consistency of the stitches seems to indicate that only one person performed the work, and as Eliza did sign the reverse and gift the quilt to Aaron Jones, Connecticut, it is more likely that it was completed by her.

.png)

Creating a Family Tree

What more can we learn about Eliza? What was Eliza’s age at making this beautiful piece? Was she married or is Murchison her maiden name? How is she related to the young Jane who created our sampler? Who is Aaron and why would she spend the time to create such a large quilt for him? Those answers and more can be answered with the information Eliza left in cross-stitching on the quilt.

There is documentation of Eliza Murchison living in Orangeburg, South Carolina in the 1830s. Further, the 1840 census lists her of leading a two-person, all-female household, and the 1860 census – which shows that Eliza was then residing in Sumter, South Carolina – lists her place of birth as Connecticut. With no male listed in these censuses, we wonder if at this time she was an unmarried woman or perhaps a widow. Without a marriage record, our only research path was through Aaron B. Jones and their shared link to Connecticut. Perhaps Aaron was a sibling or nephew, or maybe a single male Eliza hoped to one day wed?

Jones admittedly is a very common surname. However, the year (1833), city (Manchester), and the fact that he was male made it easy to find Aaron Buckland Jones, the son of Eunice Buckland and William Jones, using various census records in Ancestry.com. Digging deeper made the family connection clear: William’s brother, Samuel Phillips Jones, and his wife, Jane Bruce, had at least seven children, including Elizabeth “Eliza” Campbell Jones (1793-1870). At the age of 40, our quiltmaker, Eliza, made this piece for her first cousin.

Once we confirmed Eliza’s age, place of birth, and surname, a record noting her marriage to Roderick Murchison soon followed, and eventually so did the name of one of her children: Jane M. Murchison.

Jane does not appear in most family trees in Ancestry.com and in fact has no digitized government records associated with her name. Why is there so little information, even less than normal for women at the time? Jane passed away at the age of 10, only two years after completing the sampler. This means her sampler may have been one of the greatest personal achievements in her short life, and it is likely the only surviving material object of her existence.

Eliza and Roderick Murchison had another daughter, Roderick “Rodie” Elizabeth Murchison, who had four children, including Margaret Bruce Murchison McDonald, the mother of the donor of these two textile pieces.

The quality of the pieces indicate that the Murchison family was wealthy, and contemporary documents support this theory. Roderick’s father, Philip Murchison, was a Scottish immigrant who operated a mill along the Little Pee Dee River in Marion District, SC. Philip passed away prior to 1830, but the census recorded his wife, Margaret Ann McCrae as enslaving two people. By 1840, Eliza is the head of her own household, her husband having died in 1820. At the time she enslaved 10 people inherited from her husband and perhaps her father. She never remarried.

While we do not yet know why Eliza made this beautiful quilt for her cousin Aaron, it is due to Eliza’s forethought in signing the reverse that we are able to shed additional light on her daughter’s story, and in turn, on Eliza’s own. Eliza could not have imagined her skill with needle and thread might someday allow modern day researchers to connect with her long-deceased daughter. These small family details that were shared with Historic Columbia by Eliza's descendant, the donor of these two pieces, further helps us tell the stories of these women as we celebrate their craft and the resilience of their material possessions.

Eliza’s quilt and Jane’s sampler can currently be viewed at the Robert Mills House. Both of these items were donated by Jane McDonald in memory of her sisters, Mary and Margaret McDonald. Remember, if you have a family heirloom, be sure to create a written record of its story for future researchers.