Explore the Collection: Historic Columbia launches online collection

Monday, October 30th 2023

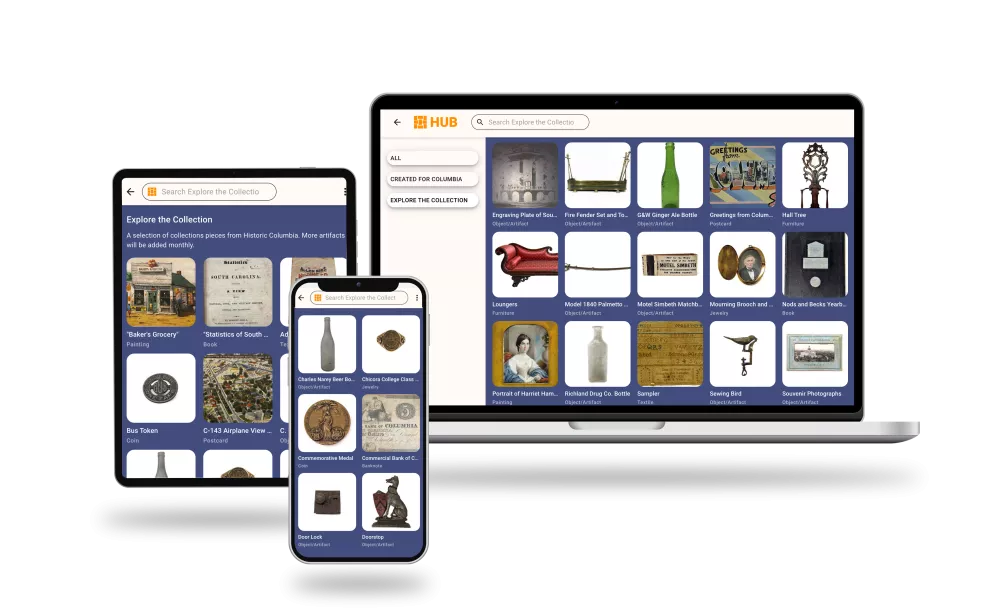

Historic Columbia (HC) recently launched a selection of 40 objects for online viewing. More objects will be added over the coming months to allow visitors from around the city, state, country, and globe to “Explore the Collection,” cared for and researched by members of HC’s curatorial team. Launching the collection online has been a multi-step process and has taken a year to prepare. From inventorying and photographing the objects to assembling data across many different platforms, selecting objects that the collections staff felt would be most reflective of HC’s collection has been rewarding. While we encourage you to view these 40 objects, and more as they are released to the public, we wanted to take you behind-the-scenes to see the process of digitization.

The objects in the collection can give us valuable glimpses into history. Museums are increasingly using modern science to gather new information about items in their collection. Examples of this include chemically examining dust remains inside jugs to identify what food source may have been stored inside centuries ago, or taking x-rays of sculptures to see if anything lies within them. But, even with something as simple as a magnifying glass, we give ourselves the opportunity to examine an object closer than before, and we may get the chance to interpret an object in ways that expand upon more than just its intended use.

When we receive an object in our collection, we carefully examine it, noting its measurements and colors. We also take notes on its condition (commonly referred to as a “condition report”), which we measure on a 5-level scale of excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor. We take the time to note any cracks, tears, discoloration, or other signs of wear. Finally, we search for any distinguishing marks. Sometimes we’re lucky and find a mark that confirms the object’s maker, date of creation, or where the item was produced, but more often than not, we rely on scholarly research or the findings of other museums to determine this information.

All information related to an object is stored in our collections management software (CMS). Over the past year, our Collections Assistant, Rachel Ward, and I have been manually migrating the information that Historic Columbia has collected over its existence about these objects into one concise location: our new CMS software, CatalogIt. Some of this information came from an earlier CMS operated by a different software company, but after many years and many different users with different methods of collections management, that software became disorganized and was not as concise and accurate as it should have been. By doing a manual migration, we have fixed these discrepancies and ensured all the information is accurate. Additional pieces of information relating to the objects came from the recollections of other HC staff and our Collections Committee members. We also combed through the original paper files first used by Historic Columbia to store this information. The recollections of people involved with HC’s collection over the years and the original paper files proved helpful for determining the provenance (history of ownership) of the objects.

Once information on an object has been recorded, we then photograph it. We can take three main types of photographs, the first being what you will mostly see in our online collection. These photos show the piece in its entirety on a neutral background so that the object itself is the focus, as well as close up images of any distinguishing marks. Another type of photograph that you may see as you explore the collection online are situ photos, which are taken in the place where the object is displayed. We have several large items in our collection, and it is often safer to limit their movement to avoid damaging them. In these instances, situs photos are more appropriate. The last type of photo we can take are close-up images to document damage to a piece. These photos allow us to track deterioration of an object over time and are not typically made public. After editing the photos, we upload them to the CMS.

.png)

When viewed in staff-mode, the CMS contains includes further records we have assembled about the donors, makers, and owners of the objects. It shows where the object is located, down to the specific drawer or box within collections storage, and allows us to track how many times the item has been on display or loaned to another institution. Any time we do anything with the object, we note it in the CMS. Not all of this information is important to visitors, and a lot of it is confidential. However, all of this data plays a role in interpreting the object and sharing its story with the public.

.png)

Finally, we get to the fun part: using all of this information to interpret the object. There are two lenses through which we typically develop interpretation: how the object was used and the context in which it was created and used. Interpretation that focuses on “use” primarily deals with objects that had a utilitarian purpose, such as fire fenders, cooking pots, and furniture. Interpretation that focuses on “context” is normally much more in-depth, as it provides detailed information on an object’s previous owner(s), its subject, or how the object was connected to a place or an event. In addition to information gleaned from the records and from the objects themselves, we use resources such as Ancestry, Find-a-Grave, other museums, online journal articles, secondary-source reference materials, and sometimes even Google Images to hunt down information about the piece. Then, after several rounds of review, this information is added to the CMS and published along with the image of the object.

Overall, the digitization project and subsequent publication allow us to share objects with the public that have been in storage for decades. While about 60% of our collection is on display (much larger than the average 2%), the remaining 40% is hidden from public view. These objects may not fit perfectly into our current interpretation, or they may be too fragile for display, but they are still valuable pieces that can help us understand Historic Columbia’s sites, our city, or our other objects. Our cloud-based CMS also supports the publication of dozens of images per object, which is extremely helpful when showing multiple pages of a book or showing multiple angles of an object, as well as preserving images of objects that may begin to deteriorate. One may not know this class ring from Chicora College was inscribed with a name on the inside, but with CatalogIt, you can get up close to an object in ways you previously could not.

.png)

The Collections team has learned a lot about the objects in our collection over the last year, and we are excited to share our findings with you! As an institution, HC has been collecting objects since 1965, and we have continued to collect several pieces in subsequent years. We focus on searching for objects with a relationship to Columbia as a whole; the Hampton and Preston families; ephemera relating to Woodrow Wilson during his family’s time living in the city; the Mann-Simons family; Modjeska Monteith Simkins; Robert Mills; Ainsley and Sarah Hall; and local artisans and manufacturers. When exploring our online collection or when visiting one of our house museums or events, be sure to consider your own family treasures. If you have something you think may be of interest to us, please consider contacting HC about a donation to Historic Columbia’s collection.

If you do have additional questions about a piece in our collection, or if you have information about an object that you think we may not know, we are more than happy to talk and learn together. With your help, and with the help of other institutions who are also able to view our collection online, we will be constantly adding to the interpretation of objects to ensure all information is as accurate as possible.

Explore the Collection

Here you can learn more about HC's collection, view the catalog online, find out how to donate items, request or share information, and read FAQs. Check back often, as we will add objects to our digital platform every month.